The Heaven or Hell Drugs | Macleans, June 20, 1964

SIDNEY KATZ

JUNE 20 1964

ON THURSDAY, JUNE IS, 1953, in the interests of schizophrenia research then being conducted in a provincial mental hospital in Weyburn. Saskatchewan. ] swallowed a chemical known as LSD-25. The tasteless, colorless, odorless substance I took had been described to me as a "hallucinogenic” drug — a drug capable of turning a normal person, temporarily, into a psychotic. My report of this unforgettable experience (Maclean's, October 1, 1953) began this way:

“For twelve hours 1 inhabited a nightmare world in which 1 experienced the torments of hell and the ecstasies of heaven. I will never be able to describe fully what happened to me during my excursion into the world of madness. There are no words designed to convey the sensations I felt or the visions, illusions, hallucinations, colors, patterns and dimensions my disordered mind revealed. . . . The faces of familiar friends turned into fleshless skulls and the heads of menacing witches, pigs and weasels. . . . The patterned carpet at my feet was transformed into a fabulous, heaving mass of living matter.

. . . I could clearly see to the horizon and beyond. . . . Time lost all meaning. . . . My senses of feeling, smell and hearing ran amok. ... At times, I beheld visions so beautiful, so dazzling, so rapturous, so unearthly that no artist will ever paint them.”

When I wrote these lines LSD and its chemical relative, mescaline, were the only hallucinogenic agents known. Today the number has proliferated to include psilocybin, DMT, UM-491, CI-395, and many more now being synthesized or tested. They have a new name, the "psychedelics.” meaning mind-revealing, mind-expanding or consciousness-expanding drugs. The term was coined by Dr. Humphrey Osmond, formerly of Saskatchewan and now director of psychiatric research for the state of New Jersey. ("To sink in hell or soar angelic, You need a pinch of psychedelic,” rhymes Osmond.) Thousands of people have taken one or another of the new psychedelic drugs. They include many people with specific problems: alcoholics, neurotics, psychotics. child schizophrenics and hardened criminals. But the consciousness-expanding chemicals have also been used by large numbers of "normal” people — writers, painters, scholars, theologians and others who believe that these new', potent agents are able to endow their lives with greater beauty, meaning and purpose.

No contemporary account of the potential benefits of the psychedelic drugs has so far been made public, even in the medical press. One reason is suggested by Dr. J. Ross MacLean of Hollywood Hospital, New Westminster. B.C., where over six hundred patients have taken LSD. "Many medical journals are now running two years behind in publishing material,” he says. “It's almost like court cases in Ontario."

They have names like LSD, UM-491, DMT. They have weird, visionary effects on the mind—glorious or utterly terrifying. They may have truly fantastic powers in treating mental illness, alcoholism, criminality. Theologians are bitterly divided over their ability to induce "instant religion." Their enthusiasts say they could even add a new dimension to the inner lives of average men and women.

But accumulated experience with the drugs up to now — both published and unpublished — has aroused excitement and enthusiasm in many informed quarters. To Dr. Duncan Blewett, a University of Saskatchewan psychologist, "The psychedelics are the strongest tools ever dreamed of for man's betterment. They will solve most of man’s problems. They can make humanitarians out of fanatics, friends out of enemies, effective people out of neurotics.” Dr. Timothy Leary, a brilliant but controversial ex-Harvard psychologist whom I recently interviewed in New York, flatly states that "the consciousness-expanding drugs can make the average person happier, wiser, kinder and more creative.” In the view of Dr. Stanley Krippner of Kent State University in Ohio, we should be exploring energetically the widest possible use of the psychedelics "if millions of people arc to be helped quickly, dramatically and inexpensively."

Dr. Abram Hoffer

This kind of buoyant optimism appears to be justified in the case of chronic alcoholics who are beyond the reach of psychotherapy or Alcoholics Anonymous. For the past ten years, alcoholism clinics in Saskatchewan and British Columbia have been blazing a pioneer trail in the use of LSD. Over a thousand patients have been treated, many of them "hopeless." Dr. Abram Hoffer, a University of Saskatchewan specialist, sums up the result this way: "LSD is the best remedy we've got. Our results are twice as good as those achieved by any other treatment program.” From the state hospital in Everdeen. Netherlands Dr. Arendsen-Hein reports what appears to be a breakthrough in the treatment of psychopathic criminals. He describes, among others, an inveterate swindler and sex pervert who was unaffected by five years of psychiatric treatment. After treatment with LSD the patient "is now such a different character that skeptics would say this is too good to be true.” After observing several such apparent miracles, Dr. Ci. W. Arendsen-Hcin says. “Our widespread skepticism as to the value of treating the criminal psychopath needs revision.” Schizophrenic children, who for years have lived silently in a remote fantasy world of their own creation, have partially returned to reality after taking LSD and UM-491.

Some theologians claim that almost everyone can have a deep, mystical religious experience with the psychedelics. R. G. Wasson of New York, an authority on vision producing agents, has described psilocybin as “the great mediator with God.” Hundreds of poets, painters, sculptors, writers anti-composers have used the mind-expanding chemicals. “They respond ecstatically and wisely to the drug experience,” says Dr. Timothy Leary. “They tell us this is what they’ve been looking for. Creative people revel in the new and intense and direct confrontation with the world about them.” Many neurotics, after drug sessions, report freedom from painful symptoms of long duration. Large numbers of “normal” people have also praised the drugs, claiming they increase the capacity to love, to communicate, and to develop one’s latent abilities.

Because the psychedelics introduce a radically new approach to mental therapy it’s not surprising that they have stirred up a storm of debate in medical and psychological circles. The most heated controversy was precipitated by the so-called “Harvard University drug scandal.”

The central figures in the Harvard affair were two staff psychologists. Timothy Leary, forty-three, and Richard Alpert, thirty-two. Their experiments with LSD and psilocybin began in I960 under the auspices of Harvard University. As their interest in the drugs intensified, they began off-campus investigations in private homes and apartments, using as their subjects graduate students, friends, doctors, theologians and an assortment of painters, writers and sculptors. By 1962 they were continually under attack by university officials, government health authorities and various members of the medical profession.

According to university officials. Leary and Alpert did not exercise the necessary caution in selecting candidates for LSD and psilocybin. “Playing with these drugs is like playing psychic Russian roulette,” said John U. Monro, dean of Harvard College. The authorities charged that several Harvard students were under medical care, the results of careless psychedelic experiments. One patient, they claimed, imagined that he was six inches tall for forty-eight hours; another took to his bed for several weeks, crying and sobbing, in memory of the horrible hallucinations induced by psilocybin. Leary and Alpert were criticized for giving potent drugs without being qualified to practice medicine. An even greater transgression in the eyes of the university was the psychologists' practice of taking psychedelics along with their subjects. “The more the two scientists take the drug.” said one critic, “the less they become interested in science.”

In the fall of 1962 Leary and Alpert organized IFIF (the International Federation for Internal Freedom) to explore the drugs, train people in their administration and set up “transcendental colonies.” IFIF is now defunct because of opposition by strong factions within the medical profession, and government health authorities. At its zenith it had three thousand members and quarters in Boston, New' York, Los Angeles and Mexico. Leary and Alpert’s dispute with Harvard University ended last summer when both men were fired by President Nathan Pusey — an unusual event in Harvard's well-ordered existence.

What the Harvard affair has underlined are the two sharply opposing professional views about how to use the mind-expanding drugs. The majority of psychiatrists, psychologists and pharmacologists tend to be conservative. As a general principle, says Dr. Theodore Rothman, a senior psychiatrist on the staff of the University of Southern California, the drugs should be used sparingly. “I’m against chemical brainwashing,” he says. “I protest the impairing of the intact human brain with chemicals in order to disorganize the nervous system, producing psychopathological states which may be irreversible.” On occasion, he has dismissed Leary and Alpert’s views as "academic hipsterism." Dr. Jonathan Cole, director of psychopharmacological research at the U. S. National Institute of Health in Maryland, told me that he favors using the psychedelics only on seriously disturbed people who have failed to respond to other forms of treatment. An important peripheral hazard of the drugs, according to Cole, is that they are “cultogenic.” What this means, he says, is that “people who take them develop boundless enthusiasm and want to give them to everybody else.” Other qualified experts have warned that if the drugs are used indiscriminately, a kind of psychic addiction may be set up in some people. Present government control of the psychedelic drugs reflects this fear. Restrictions on distribution of the chemicals are rigid, both in Canada and the United States.

No one who has had personal experience with any of the consciousness-expanding chemicals will question the need for caution. They should be administered by competent specialists, and withheld from people who want them only for “kicks.” They should never be given unstable individuals in whom they might precipitate a psychotic breakdown. With these reasonable precautions, medical men who have actually worked with the drugs have shown that when they are professionally administered the risk involved is negligible. Fortunately. all but a few people seem to be able to take the new chemicals without harmful effects. After reviewing one thousand published studies on LSD, Drs. Sidney Cohen and Keith Ditman, of Veterans Hospital in Los Angeles, concluded that LSD is nonaddictive and that toxic or psychological complications from its use are rare. The statistically small proportion of people who have suffered damage have usually been those who bought the drugs on the black market and took them without supervision. A pioneer in LSD treatment. Dr. Abram Hoffer adds, “There is no danger to the subject. In most cases where there have been bad results this may be ascribed to the incompetence of the people giving the compound.”

“To restrict their use to the ill is analogous to saying that only the sick should be able to go to Paris for a rest and change”

Still, many or possibly most medical authorities continue to claim that psychedelics should be administered only to people suffering from serious mental illnesses. Dr. Duncan Blewett. of the University of Saskatchewan, thinks otherwise. “To restrict their use to the ill is analogous to saying that only the sick should be able to go to Paris for a rest and change. It may help a sick man to overcome his disease, but a man who is well to begin with is likely to see and accept far more and to profit far more from the trip.” And the attempt to restrict the psychedelics is viewed by Dr. Timothy Leary as a serious encroachment on individual freedom. “People should have access to their own nervous systems and their own unconscious minds,” says Leary. “That’s the fifth freedom.” Leary says he is not surprised that the new chemicals are regarded with suspicion, fear and hostility by most orthodox medical and scientific people. "All pioneers and trail-blazers can expect to be persecuted.' he says. "We are visionaries. far-out explorers in an exciting new world.”

Leary's world had its modern beginning one April afternoon in 1943 in a laboratory in Basel. Switzerland. Albert Hofmann, a chemist employed by the pharmaceutical firm Sandoz AG, w'as trying out different compounds based on lysergic acid, a chemical derived from ergot, a black fungus that grow's on rye and wheat. Hofmann swallowed a small quantity of a compound he had just created, later to become known as LSD. "1 experienced fantastic images of an extraordinary plasticity," he later reported. “They w'ere associated with an intense kaleidoscopic play of colors. . . . Space and time became disorganized. ... I thought I had died. My ‘ego’ was suspended somewhere in space and I saw my body lying dead on the sofa. ... I was overcome with fears that I was going crazy.”

Hofmann's strange new compound aroused the immediate curiosity of medical scientists throughout the world who were interested in mental health. They learned that LSD dilates the pupils, raises the systolic blood pressure, increases the strength of reflexes and of electrical discharges from the brain. It also stimulates the brain's sensory centers as well as blocking off its inhibiting mechanisms. Most significantly, LSD and variations of LSD compounds can inhibit or encourage the production of serotonin, a substance found in certain regions of the brain. Some researchers suspect that hallucinations and agitated behavior result from an excess of serotonin, and that fits of depression and catatonic states result from a deficiency of serotonin.

A few years after his LSD discovery Dr. Hofmann created psilocybin. the pure chemical form of the active ingredient of the famous vision - producing mushroom, Psilocybe mexicana. Other chemists synthesized mescaline, derived from the peyote cactus plant found growing in large sections of the southwestern United States, Mexico and Central and South America. Mescaline is chemically related to LSD as are DMT and UM-491, two other newly arrived psychedelics. All these chemicals are usually administered in tablet or liquid form. Another new drug. C1-395 or Phencyclidine, is administered intravenously. The strongest of all the psychedelics is LSD, one hundred times more potent than psilocybin; seven thousand times stronger than mescaline. The effects of LSD last eight to twelve hours: psilocybin four to six hours: DMT about an hour.

The action of the psychedelics on the human body is yet to be explored fully, as are the means by which the new chemicals bring about phenomenal changes in the feeling, thinking, attitudes and behavior of many of the people who take them. I will, however. attempt to summarize the explanations of several physicians, philosophers and theologians. The explanation will be inadequate. No written language exists to convey fully what happens to a person who takes a mind-expanding chemical.

Under the influence of the drug the subject has what workers with psychedelics have come to describe as a "transcendental experience,” an experience "beyond the person." It is overwhelming and illuminating, both emotional and intellectual. It is often likened to the Zen Buddhist idea that an adept can achieve, after years of prayer and meditation, a satori —an “experience of experiences” powerful enough to change a man's life. The change, according to Zen, involves a keener and deeper perception of the self and the world: a greater zest and appreciation for "oneness" in life — nothing is alone or unimportant. An adept in satori should become more understanding, more sympathetic, more tranquil.

Psychedelic drugs, according to their proponents, make most people capable of a satori without the Zen adept's years of earnest prayer, meditation and ascetic practice. (This has prompted one observer to refer to LSD and psilocybin as "instant Zen.")

The drug is the key to a new. limitless world in which mental blocks and barriers vanish. The subject's capacity to lie to himself or to rationalize his failures disappears. His new inner perception enables him to reconstruct his future life along different lines. In religious terms, a "conversion" has taken place: the individual has died and been born again.

The treatment of alcoholism with psychedelic drugs provides the most striking example of the constructive powers of a "conversion" by psychedelic dosage. In the last ten years a few' thousand alcoholics have been treated with LSD in clinics in Canada, United States and Great Britain. An analysis of all the available statistics shows that LSD in combination with psychotherapy, caused half the treated alcoholics to become abstainers: psychotherapy alone succeeded with slightly less than one patient in three.

The idea that an overwhelming mystic experience can dramatically alter the course of a man’s life is hardly new. Sixty years ago the philosopher William James said. "The cure for dipsomania is religiomania.” As early as 1907, American anthropologists reported that drunken, degenerate Winnebago Indians who began taking mescaline as part of their religious rites became "sober, successful, healthy, outstanding members of their community.” The same has been true of Canadian Indians who belong to the Native American Church on the Prairie Provinces. It's interesting to note, too, that Alcoholics Anonymous — the first group in modern times to cope successfully with alcoholism — has a strong underlying religious motivation: the patient has to admit his helplessness and place himself in the hands of a “higher power.”

A thirty-eight-year-old patient in a Saskatchewan clinic was described as "a hopeless alcoholic, who. for years, had been drinking forty ounces of whisky a day.” His father had been a chronic drunkard. The patient frequently suffered DTs and was often depressed and suicidal. He had been in prison for passing bad cheques. He was not supporting his third wife. All previous treatment had failed. After taking LSD, he wrote. "I felt different about myself and others. I began to realize all the people I had lied to. the jobs I'd lost and the people I'd affected. I couldn't look in the mirror because I didn't like what ! stood for." After leaving hospital, he stopped drinking, graduated from university and is today successfully filling a highly skilled job.

At the mental hospital in Weyburn a forty-seven-year-old man with a lengthy history of alcoholism and petty crime was given LSD. Later he said, "I find it hard to describe what took place after forty-seven years of beating my brains out against a wall of indifference, self - centredness and ignorance plus the inability to believe there could he a power bigger than me. Today that wall was ripped apart. I will never be able to describe that exquisite, beautiful moment of my life of accepting and being accepted. I am still amazed at the exquisite feeling of release and peace of mind which took place at that moment.”

Dr. Charles Savage of the Mental Research Institute in Palo Alto, California, describes an alcoholic woman who was given 150 micrograms of LSD. She closed her eyes and seemed to fall in a trance. Then she awoke with a start and said, “I thought I had been killed. I thought I was tried, dragged in chains before God, condemned and taken out to be executed.” She awoke, feeling that she had been reprieved. She stopped drinking and has been abstinent for three years.

Many scholars and scientists have attempted detailed explanations of how these changes in behavior come about. The opinion of Dr. Eric Fromm is often quoted, that the alcoholic is a person “alienated” from society, suffering from a “sickness of the soul.” He feels lost and rootless in our industrial society. He seeks his salvation in alcohol. But the attempt fails and now he’s trapped by drink. “After the LSD experience,” says Dr. Charles Savage, “the subject awakens with a feeling of rebirth. He is provided with a new beginning, a new sense of values.” After long observation, Dr. S. E. Jensen, director of the York County Mental Health Unit in Newmarket, Ontario, has concluded, “The conversion of the alcoholic under LSD is not conversion to a particular church or doctrine. It is the experience and knowledge that a higher power exists, and with this comes the humility which many experts agree is so important to maintaining sobriety.”

The man who takes a psychedelic drug can be encouraged to have a transcendental experience by psychological preparation. This was not known when I took LSD eleven years ago. I was told in advance, repeatedly, that I was about to embark on a nightmarish journey into the unknown world of psychotic madness. I took the drug in a hospital, surrounded by white-coaled doctors. My experience in the drugged state was overshadowed by terror.

It remained for the former Harvard psychologists, Drs. Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, to discover that the mind-expanding experience can be “heavenly or hellish” depending on what kind of advance preparations are made. Their own LSD and psilocybin sessions were customarily held in rooms heavily draped with batik silk and hung with abstract paintings and collages; dim light and soft music filled the room. Later, when they shifted their operations to the Mexican fishing village of Zihuatanejo, the drug rooms, decorated with woven Hindu prints, overlooked the palm-studded beach and were within sound of the Pacific Ocean.

Psychological preparation for a drug session is based on helping the subject find answers to the questions, “What are my problems? In what ways do I want the mind-expanding drug to change my attitudes and behavior?” Leary believes that most people are rigidly committed to playing a personality “game” — engineers play the “engineer game”; salesmen play the “salesman game.” Each game has its own set of rules, values and jargon, and sticking to the rules often means a man never fulfills his deeper needs. The psychedelic drug is a key to freedom from the stereotypes of the game, says Leary.

Leary and Alpert have also adopted their own version of a mystic Tibetan work, The Book of the Dead. (Their taste for borrowing phrases and ideas from Eastern mysticism probably helps explain why Harvard excommunicated them and why they sometimes sound more like beatniks than scientists even to a layman.) Written several centuries ago, the original

volume was a book of instruction on the art and science of dying, the mysteries of life after death and reincarnation. Leary and Alpert use their version to guide subjects on how to lose their ego (“psychic death”) and then live again (“psychic rebirth”) .

During a drug session a guru (Hindu for guide or teacher) joins the subjects in taking a dose of the drug — usually much smaller in quantity. The guide’s role is to allay fear and help the subject make his way among the intricacies of the transcendental world. At times the guide reads passages from The Book of the Dead: “Trust your divinity . . trust your brain . . . trust your companions . . . float downstream.”

The psychedelics are being used against several forms of what has been regarded as “incurable and helpless” human conditions. One of these conditions is criminality. In one experiment conducted on thirty - six criminals at Concord Reformatory, a maximum security prison in Massachusetts, men who had been given psilocybin while in prison showed a recidivist rate, eighteen months after they had been released, only half as great as the general one for Concord prison. “The drug seems to break up the pattern of criminality,” Dr. Leary says. But he advised other forms of therapy as well.

Another “incurable and hopeless” human condition the psychedelics are being used to fight is childhood schizophrenia. The childhood schizophrenic has long been a baffling and insoluble problem to the psychiatrist. The disturbed child lives in a secret and frightening world of his own making. His perceptions are distorted; he doesn’t respond to people or things in his environment. Often he sits or stands alone rocking, whirling, staring at his fingers, banging his head against a wall or pounding himself

with his fist. His sleeping, eating and toilet habits are disorganized. Some such children are “autistic” — meaning that their “language” is limited to screams or a few guttural sounds. Other schizophrenic youngsters are “verbal”; they possess some skill with words but they are unable to distinguish between their terrifying nightmares and reality. One such boy said. “Once 1 stared at a kid. He was real small and then he got bigger and bigger each minute. I looked at him and he turned into a giant.” Another boy came to believe that a person in his stomach was controlling him.

Many such children are hospitalized at the Creedmoor State Hospital in Queen’s Village, New York. They have all failed to respond to all the known treatments — psychotherapy, electric and insulin shock, tranquilizers, energizers, antihistamines and anticonvulsants. On an experimental group of fifty of these youngsters between six and twelve years of age — half of them autistic, half verbal — Dr. Lauretta Bender and her colleagues decided to try two psychedelic drugs, LSD and UM-491. They dosed the children every day for periods ranging from two to twelve months.

The changes in the autistic children, according to the report prepared by Dr. Bender and her group, were “most remarkable.” They became happier, sometimes gay, particularly in the early stages of the treatment. Some showed by their facial expressions that for the first time they knew what was going on around them. Parents and hospital staff said the children were “more affectionate,” “more aware” and “less afraid.” A boy who was usually under sedation because he beat himself severely could now get along without his daily sedative. Sleeping and eating habits improved: the children gained weight and acquired a healthy

color. Several youngsters became interested in speech for the first time. Some actually began to make themselves understood.

There were also improvements in many of the "verbal” children. A hostile, sullen boy began greeting the hospital staff with a smile and a pleasant remark. Several of the youngsters were now able to distinguish between their fantasy world and reality. One boy, speaking of his past hallucinations, explained, "That's when I w'as sick.” Another said, “I w;as acting crazy then, like a cartoon.” These improvements were maintained only while the LSD and UM-491 treatments continued. When the drugs w'ere stopped the children's condition deteriorated, but not to its former level. With resumption of the drugs came improvement again.

To Dr. Bender and her associates the dramatic effect of the psychedelic drugs on schizophrenic children is encouraging. Here, at last, is a substance w'hich can quickly and safely bring such a child at least partly into touch with reality. The researchers say the way is now open for a series of promising biochemical studies: how do the psychedelic drugs produce such a "healthy” result? Can the psychedelics be used helpfully in combination with other chemicals? "Hopefully,” Dr. Bender says, "these drugs will contribute to our efforts to find better therapeutic agents for early childhood schizophrenia.”

But numerically, at least, it's safe to predict that a less seriously deranged group, neurotics, will be the great beneficiaries of the consciousness-expanding drugs. The ability of psychedelics to help emotionally ill people achieve insight has been described as "thrilling” by Dr. James Terrill of the Mental Research Institute at Palo Alto in California. The psychedelics, he says, can bring about personality changes unobtainable by traditional methods. “LSD has a lot to offer, particularly to those over-controlled individuals who cut off their feelings and tend to seek intellectualized answers to all the problems of life. LSD helps make them whole again." Case histories from the files at Palo Alto underline the potential healing powers of the new drugs.

A staff physician at the clinic. Dr. Donald Jackson, was consulted by a brilliant professor whose future looked bleak because he was overwhelmed by an ever-present fear of insanity. Some years before, he had taken his problem to a celebrated psychoanalyst who told him that he was a "pseudoneurotic schizophrenic-’ and therefore “unanalysable." The professor was left for years to alternate between lethargy and desperation. During his first LSD session he talked freely of his terrors. In the second session he plunged boldly into the psychotic state and became so wildly agitated he had to be forcibly restrained. "Together we came face to face with the insanity he had feared and together we mastered it,” says Dr. Jackson. "He found a phantom he could discard: he also found his real self, a living human being.”

At the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park. California, LSD is used routinely in treating patients who are emotionally disturbed as w'ell as in trying to help businessmen, teachers, writers, and others who simply want to reconstruct their lives along broader, richer lines. According to a recent report, eighty-three percent of 113 patients claim to have found "lasting benefits.” The results most frequently mentioned are decreased feelings of guilt, anxiety and inadequacy; freedom to use one's abilities: improved relationships with other people and greater freedom to communicate with others.

Dr. M. J. Rejskind. director of the Regina Mental Health Clinic, has repeatedly observed the remarkable tongue-loosening quality of LSD. He describes an unhappily married couple with five children who were unable to talk honestly with each other about the causes of their difficulties. Rejskind gave both husband and wife LSD together. As the drug took effect they began talking about each other with utter frankness. "For the first time they began to realize how they felt about themselves and about each other,” says Rejskind. The couple is still seriously mismatched but husband and wife now tolerate each other good-naturedly. Rejskind is beginning to use LSD to spark discussion among a group of eight depressed patients who, left to their devices, look at each other in glum silence. LSD, according to the initial results observed, has turned them into chatterboxes. “They’ve gone overboard.” says Rejskind. "They’re talking freely without fear.” Despite these results with LSD. Rejskind firmly believes that psychotherapy will always be the backbone of treatment of the emotionally disturbed. “You can't replace a skilled therapist with a miracle drug.” he says.

The psychedelic drugs may come to be an important element in treating troubled high school and university students. Under-achievement and drop-outs now involve many highly intelligent but troubled students. A 1963 mental health survey of University of Toronto students reported that three students had committed suicide while a dozen others had unsuccessfully tried to do so. At least four hundred young men and women had sought psychiatric help. Many of them had become dependent on pep pills and tranquilizers. Despondency, depression and deep concern over such problems as personal relationships, sex, friction with parents, pressure from parents to do well, the need to conform, the quest for meaningful values and the inability to communicate were found to be widely prevalent. Commenting on the shortage of psychiatrists, a university health official observed. “A lot of drop-outs might have been saved had we got to them early enough.”

Psychotherapy is one way of “getting" to them, but it has the disadvantages of being expensive and slow even when a psychiatrist is available. An alternative, according to Dr. Stanley Krippner. a Kent State University psychologist, is treatment by psychedelic drugs. He cites the case of a fifteen-year-old high school drop-out, a highly intelligent boy. “He was irresponsible. indifferent about his studies and personal appearance and got into difficulty with the law. After being out of school a year, he received a psychedelic drug. The lad finds it hard to explain the overwhelming effect it had on him. "It liberated a power in me I knew I had but couldn't use.” he said. "I now' feel different about things.” The boy returned to school and established a reputation as a first-rate scholar and a responsible, well-liked leader.

Apart from doctors, theologians have shown the greatest interest in and curiosity about the consciousness expanding drugs, as well as the most energetic tendency to dispute their usefulness. Psychedelic subjects often use religious terminology and concepts in trying to describe their experiences. After taking psilocybin, the majority of a group of sixty-nine ministers and religious workers said they had rich spiritual experiences. Another group drug session conducted by Dr. Timothy Leary involved four hundred volunteers — graduate students, professors, writers — only ten percent of whom were orthodox believers or churchgoers. Yet, in re-calling the experience, more than half used terms like “God," “divine," “meeting the infinite," “the oneness of the universe” and “resurrection.”

Even half of the tough criminals in the Concord Reformatory experimental group mentioned earlier reported mystic conversion reactions.

Ten theologians took psilocybin on Good Friday. Nine underwent “a genuine religious experience"

The same theme runs through individual accounts of the psychedelic experience. Robert Graves, the eminent English poet and scholar, says, “I entered the Garden of Delight. I am not talking in metaphors nor am I a mystic. Paradise is where I went. The man w'ho enters . . . will never be quite the same man when he returns.” Under the influence of the drug, Wilson Van Dusen, a California psychologist, recalls, “I was in a black void in which God was walking on me and I cried for joy. My voice seemed to speak of His coming but I didn’t believe it. Suddenly and unexpectedly the void was lit up with the blinding presence of the One. How did I know? AII I can say is that there was no possibility of doubt."

To find out whether the psychedelic transcendental experience was similar to the experiences reported by religious mystics and saints, a Harvard theologian organized a controlled experiment. It was conducted at noon on Good Friday of 1962 in Marsh Chapel, located in the basement of Boston University. The subjects were twenty divinity students, half of whom took psilocybin; the other half took dummy pills. A minister delivered a sermon and left the group alone in the room which was filled with organ music. During the next three hours nine of the psilocybin group reported “a genuine religious experience.” Only one of the control group reported the same thing. A typical account was, “I felt a deep union with God ... I carried my Bible to the altar and tried to preach. The only words I mumbled were peace, peace, peace. I felt I was communicating beyond words.”

“Dr. Timothy Leary predicts that “the day will come when sacramental biochemicals like LSD will be used as routinely as organ music and incense to assist in the attainment of religious experience.””

In the past, visions, ultimate knowledge and other forms of religious ecstasy have been achieved only by a handful of holy men after years of meditation and prayer and lengthy periods of fasting, isolation, controlled breathing exercises, seclusion or sleeplessness. The psychedelics, as it were, appear to bring mystical experiences within the reach of almost everybody. “This is a necessity in our modern culture,” says Dr. Stanley Krippner, the Kent State University psychologist. “Most people today are not deeply moved, spiritually, by attendance at church.” Dr. Paul Lee of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a former Harvard divinity student, observes. “Everyday religious experience has become so jaded and rationalized that to become aware of the mystery and wonderment of life we must resort to drugs.” Dr. Walter Houston Clark, of the Andover Newton Theological School, deplores the lack of spiritual closeness and fellowship among church members. The fellowship in the modern church, he says, “hardly exceeds that to be found in a Rotary Club or a closely knit business.” Groups who have been “illuminated” together, he believes, would acquire this desirable kind of rapport and cohesiveness. Dr. Timothy Leary predicts that “the day will come when sacramental biochemicals like LSD will be used as routinely as organ music and incense to assist in the attainment of religious experience.”

Most theologians dispute these hopeful opinions. When they refer to psychedelic drugs they tend to use phrases like “instant mysticism,” “instant grace,” “instant salvation," “chemical religion" and “cheap and lazy religion." The Presbyterian head of the San Francisco Theological Seminary, Dr. Theodore Gill, says that “the drugs make an end run around Christ and go straight to the Holy Spirit." Other churchmen hold that the use of chemicals amounts to “irreverently storming the gates of heaven.” The distinguished Oxford authority on Eastern religions, R. C. Zaehner, says that while drug-induced revelations are strange and inexplicable they are far different from the ecstasies of the saints and holy men. One thing can be said for certain: the advent of the psychedelics has posed a number of serious theological questions which urgently need answering.

As Joseph Haven says in his thoughtful paper, A Memo to Quakers on the Consciousness-Changing Drugs, "Seldom has the demand for rethinking of the nature of mystical, experimental religion been so insistent."

Much of this rethinking is under way. Scholars have traced, in detail, man’s long history of eating plants and vegetables to induce religious visions. About twenty-one hundred years ago — one theory holds — the Aryans of Central Asia were habitual users of soma, a milkweed-like creeper that brought on a visionary state of mind. When they moved south to invade India they left behind their natural supply of soma. Lacking a biochemical means to induce visions they invented a system of breathing and psychological exercises — Yoga — to achieve the same result. Other ancient peoples also made sacramental use of such visionary plants as coca, opium and hashish.

In the New World several peoples incorporated roots, herbs, cacti or mushrooms into their religion because taking them produced a "oneness with the gods.” The most highly regarded has long been the sacred mushroom. psilocybe mexicana. Psilocybin and LSD pills contain the active ingredient of the sacred mushrooms in synthetic and concentrated form. Recently a scientist visited a Mexican village and gave a supply of psilocybin pills to the local curandera, or medicine woman. She was delighted with both their potency and utility. “Now I can do magic all the year round. I don't have to wait for the mushroom season,” she said.

Real ecstasy — or just a psychosis?

A fiercely debated point in the "chemical - religion'’ controversy is whether “artificial” drug-induced ecstasies are the same as “natural” ones. Many, if not most, theologians answer that the so-called revelations are probably nothing more than the symptoms of a temporary psychosis. But William James, who himself experimented with the visions induced by nitrous oxide, said in 1902 that chemical mystic experiences are “genuine.” A leading contemporary authority on mysticism, Dr. W. T. Stace of Princeton University, argues that the church shouldn't dismiss anything that has the power to deepen faith. "The fact that the experience is induced by drugs has no bearing on its validity,” he says. Dr. Houston Clark, the theologian quoted earlier who himself has taken psilocybin, concurs. "If the psilocybin experience is not at times mystical in nature, then the difference is so subtle as to be indistinguishable.”

Scientifically minded protagonists in the chemical-religion debate arc exploring the biochemical origins of both the artificial and natural mystic experiences. "We know,” writes Dr. Walter Houston Clark, "that any profound emotional experience, religious or otherwise, is accompanied by change, particularly of a chemical or hormonal nature. Furthermore, we know that the natural chemistry of the body includes biochemical substances known as the indoles which are similar in structure to the consciousness expanding chemicals. The question that then immediately arises is whether a natural excess of indoles might not predispose some people to certain kinds of mysticism? Or whether a mystical state of mind might not. on the other hand, stimulate chemical changes in the body?"

What can be stated with certainty is that ascetic practices alter the body chemistry which, in turn, radically influences perception. The holy man who fasts or a prolonged period sutlers a vitamin deficiency. Until this century, many patients committed to lunatic asylums as hallucinating schizophrenics were really suffering from dietary-deficiency diseases like beriberi or pellagra. The yoga who breathes deeply brings about an abnormal concentration of carbon dioxide in his blood which leads to marked changes in feeling and thinking. The hermit who lives in an isolated and darkened cave for several weeks has startling visionary experiences. The same thing has happened to Canadian and American scientists who exposed themselves to “sensory deprivation" by living, for several days, in a darkened chamber or immersed in a sphere underwater.

Will the new chemical religion gain wide acceptance? The California psychologist Wilson Van Duscn, a religious man. believes that chemical religion is uniquely suited to the tempo of North American life. "I'd prefer quiet years of meditation in a monastery." he says "but in the Western world we simply haven’t got the time.” Nevertheless, most religious people have a strong aversion to linking religion, in any way, to chemicals. Clark, the theologian, believes that sooner or later they’ll have to overcome this distaste. “The mystic implications of the psychedelic drugs,” he says, “cannot be ignored by theologians or leaders of organized religion.”

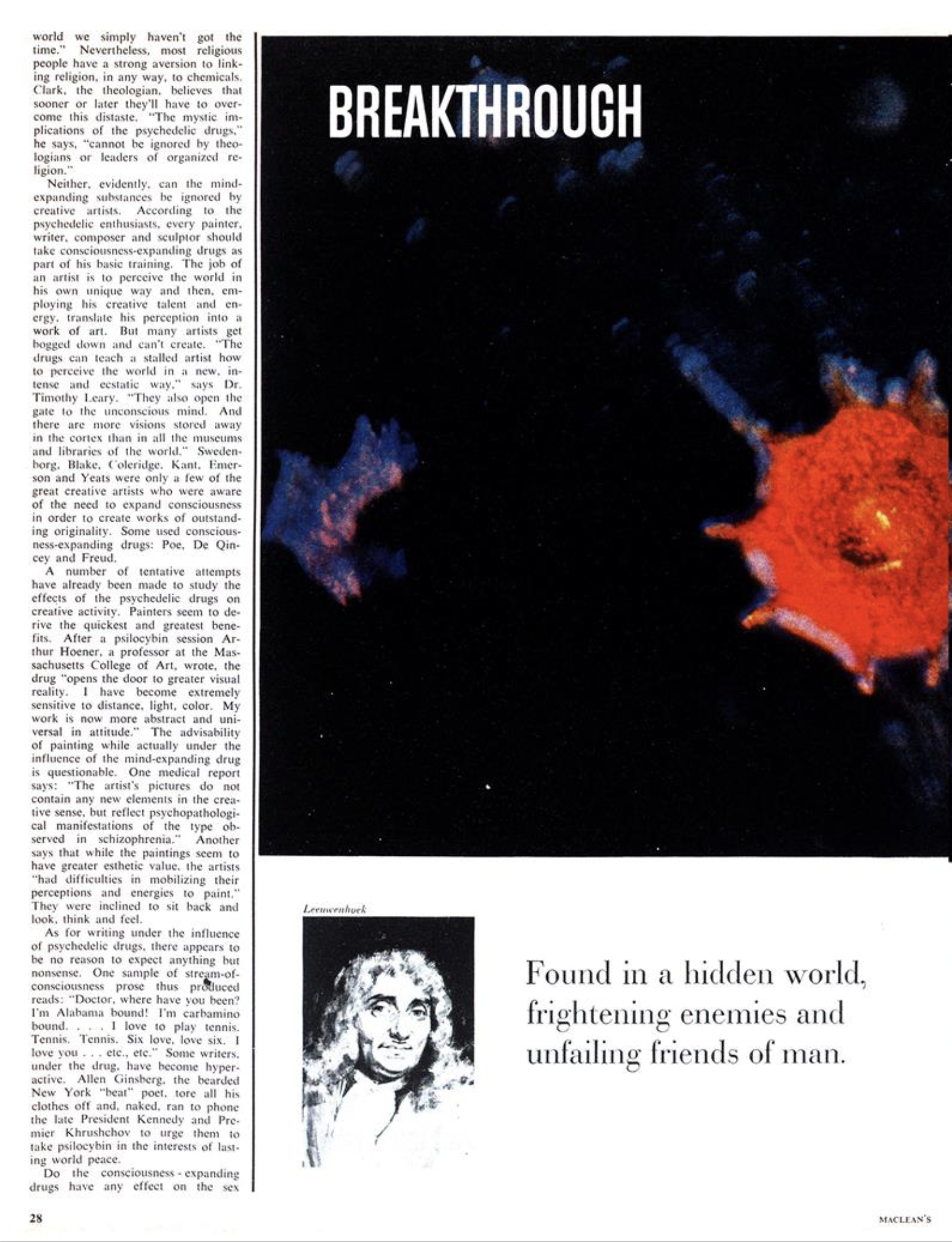

Neither, evidently, can the mind expanding substances be ignored by creative artists. According to the psychedelic enthusiasts, every painter, writer, composer and sculptor should take consciousness-expanding drugs as part of his basic training. The job of an artist is to perceive the world in his own unique way and then, employing his creative talent and energy, translate his perception into a work of art. But many artists get bogged down and can’t create. “The drugs can teach a stalled artist how to perceive the world in a new, intense and ecstatic way,” says Dr. Timothy Leary. “They also open the gate to the unconscious mind. And there are more visions stored away in the cortex than in all the museums and libraries of the world." Swedenborg, Blake, Coleridge, Kant, Emerson and Yeats were only a few of the great creative artists who were aware of the need to expand consciousness in order to create works of outstanding originality. Some used consciousness-expanding drugs: Poe, De Qincey and Freud.

A number of tentative attempts have already been made to study the effects of the psychedelic drugs on creative activity. Painters seem to derive the quickest and greatest benefits. After a psilocybin session Arthur Hoener, a professor at the Massachusetts College of Art, wrote, the drug “opens the door to greater visual reality. I have become extremely sensitive to distance, light, color. My work is now more abstract and universal in attitude.” The advisability of painting while actually under the influence of the mind-expanding drug is questionable. One medical report says: “The artist's pictures do not contain any new elements in the creative sense, but reflect psychopathological manifestations of the type observed in schizophrenia.” Another says that while the paintings seem to have greater esthetic value, the artists “had difficulties in mobilizing their perceptions and energies to paint." They were inclined to sit back and look, think and feel.

As for writing under the influence of psychedelic drugs, there appears to be no reason to expect anything but nonsense. One sample of stream-of-consciousness prose thus produced reads: “Doctor, where have you been? I’m Alabama bound! I'm carbamino bound. ... I love to play tennis. Tennis. Tennis. Six love, love six. I love you . . . etc., etc." Some writers, under the drug, have become hyperactive. Allen Ginsberg, the bearded New York “beat” poet, tore all his clothes off and. naked, ran to phone the late President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchov to urge them to take psilocybin in the interests of lasting world peace.

Do the consciousness-expanding drugs have any effect on the sex drive? So far the answers are inconclusive. Many subjects become so fascinated by the strange technicolor world they have just entered that they become disinterested in everything else, including sex. A sterile environment, such as a hospital room, would most certainly act as an anaphrodisiac. On the other hand, after taking psilocybin or LSD in their own homes, twenty-five married couples reported a remarkable intensification of the sexual experience. The report from which this information was taken — prepared, but not published, by the Harvard Psilocybin Project — speculates that the drug heightens sexuality because it releases both man and woman from inhibiting “neurotic blocks.” Furthermore, the drugs create “profound feelings of interpersonal communion and unity which endow every action with beauty and significance." The partners’ distorted sense of time may also contribute to the intensity of the experience. A minute under the influence of LSD can seem to be hours of ecstacy. Couples who have made love after taking a psychedelic have used such terms as “cellular orgasm,’’ “pulsating energy patterns,” “internal fireglow" and “melting and flowing of the entire body.”

What is the future of the psychedelic drugs? Will they be given a full and fair opportunity to demonstrate their usefulness? At present, experimental and therapeutic programs involving the mind-expanding chemicals are in low gear because of the traditional cautiousness of the medical profession. Medical conservatism has an extremely useful function; it has often kept dangerous discoveries away from the public they might have harmed. On the other hand, unreasonable caution can work against the public interest by hampering the development of new' techniques which can advance human health. Dr. J. Ross MacLean of Hollywood Hospital in New Westminster. B.C., is one of several experienced physicians who are convinced that the psychedelics are well on their way to universal acceptance. “We are now receiving patients from all over the world. many sent by highly reputable doctors and psychiatrists. The large number of really remarkable personality changes wrought not only by us but by others in North America. Europe and the Iron Curtain countries cannot remain hidden, cannot be denied forever.” MacLean says.

In our society man has become in some ways a stranger to himself. His place as an individual has become unclear. He is the victim of a variety of confusing and conflicting pressures. Countless troubled men and women are driven to seek salvation in alcohol, addictive drugs, and psychosomatic or psychic illness. These imperfect methods of salvation usually lead to the couch, the hospital or the grave. Our present conventional psychological tools for rescuing the victims of modern society are no longer adequate. We must explore new' possibilities. Among the brightest of the new possibilities are the psychedelic drugs. Hopefully, they may give man access to the vast reservoir of strength that lies in the innermost reaches of his consciousness. ★