Desert Siteworks (DSW)

Origins

From 1992 to 1994, William Binzen, a photographer, organized events at Black Rock Desert that helped guide Burning Man towards an artistic vision. The Baker Beach Burning Man celebrations were limited to the burn itself (preceded by a family picnic of sorts). And first few years in the desert Burning Man was little more than a costumed cocktail party with guns in the desert, thrown by the Cacophony Society with fire courtesy of Larry Harvey. But Binzen, along with Pepe Ozan, brought an artistic element that is one of the clearest seeds of the event we know today.

Prior to Binzen's creative direction and Ozan's sculptures, the Burning Man event was a costumed cocktail party guns on the playa

Binzen first attended a Burning Man gathering in 1990, its last year at Baker Beach. Also in attendance that year were John Law, P Segal, Kevin Evans and others from the Cacophony Society. Binzen introduced himself to Larry Harvey at the gathering, and briefly discussed ideas around art.

Binzen, had visited the Black Rock desert in 1977, had a vision of hosting an art gathering, consisting solely of contributing artists. In 1992 he first realized his vision of an art gathering on the playa by hosting the first Desert Siteworks (or DSW), with the involvement of John Law, Michael Mikel and other Cacophony members.

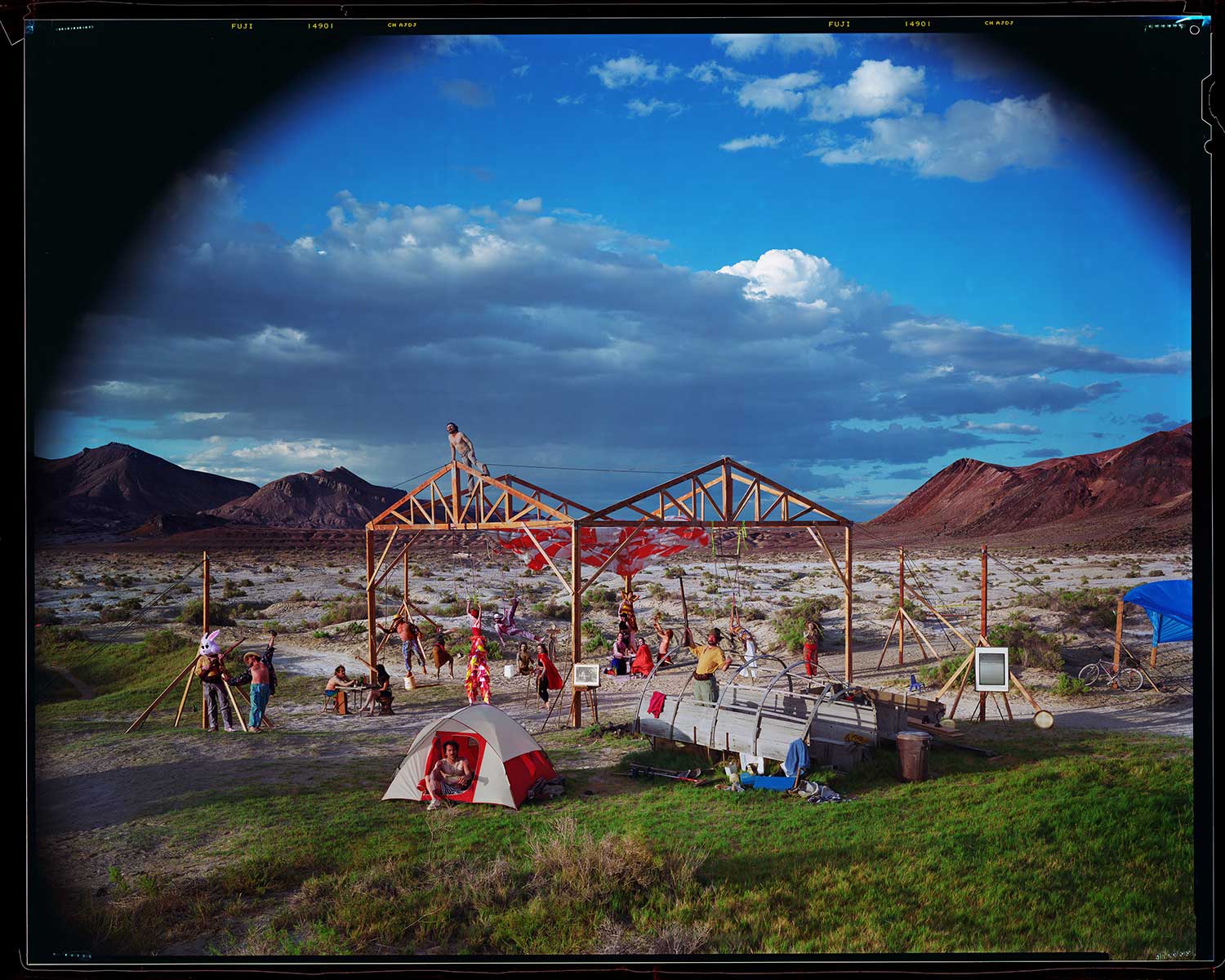

Desert House, 1992

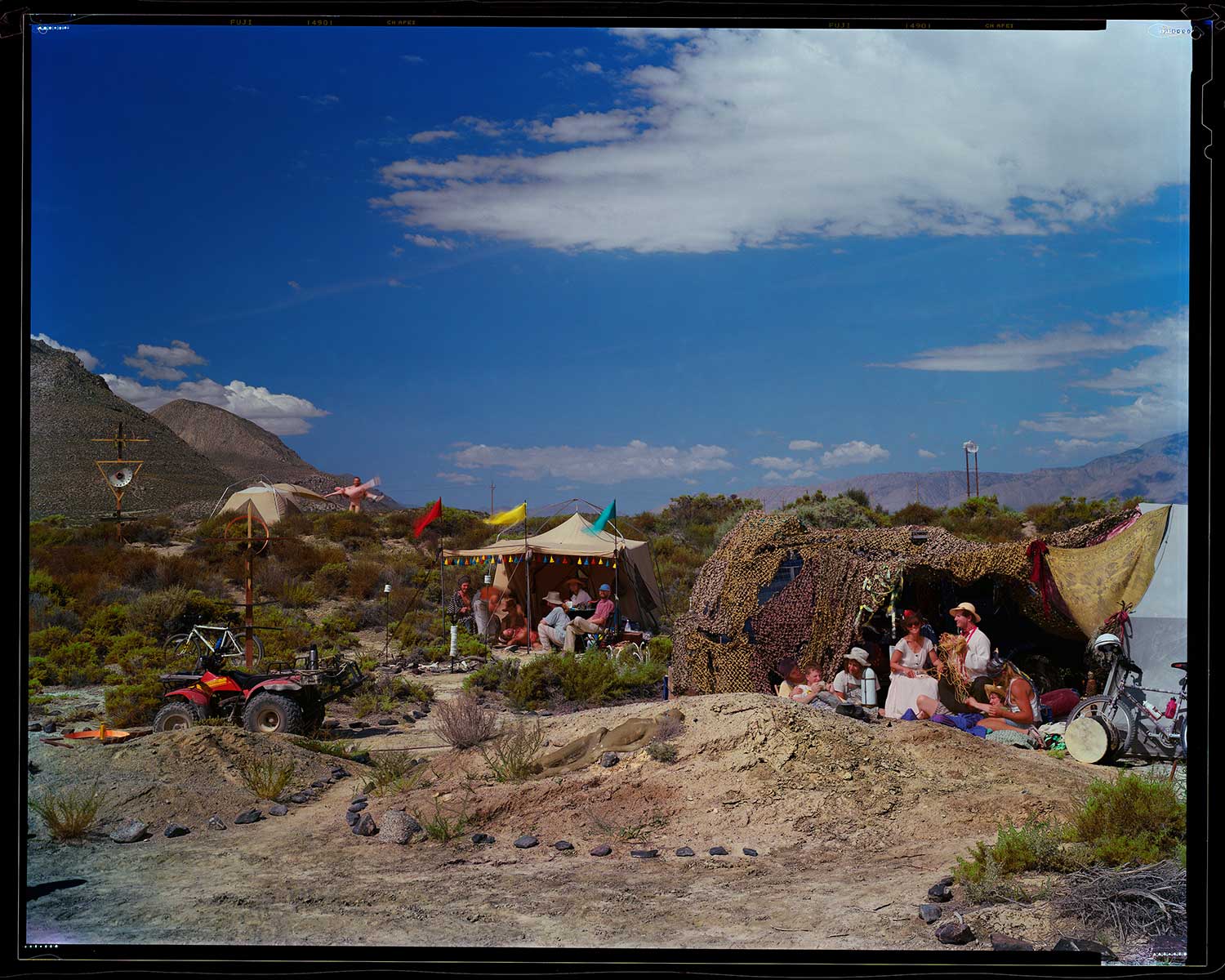

DSW

The first gathering was held on the summer solstice at Black Rock Springs with about 20 participants, mostly Cacophony Society members. At the 1992 event Binzen created “Desert House”, a public gathering place during the DSW event. He brought this back to Burning Man over Labor Day a few months later.

Pepe Ozan’s Lingam, Desert Siteworks, 1993

In 1993, Binzen and Judy West produced the event at Trego Hot Springs, with about 100 participants.

West had met William Binzen at one of the first Madrina Group meetings, when they were organizing to buy the old Best Foods factory across the street from Project Artaud. Through her contacts there, and by combing the San Francisco Open Studios weekends (an event, which is still ongoing, in which artists open their studios to the public), Binzen and West recruited a number of accomplished professional artists and performers. This group of exceptional creators combined with the much looser, amateur, yet outrageous sensibilities of Cacophony proved to be influential on the burgeoning Burning Man aesthetic and culture. Nothing anywhere remotely as ambitious or involved as the Trego Springs DSW project at Summer Solstice, 1993 had yet been attempted at Burning Man.

In mid-summer 1993, Pepe Ozan first built the first Lingam at Desert Siteworks out of local clay at Trego. Ozan returned in August 1993 to build a larger one at Burning Man on the main playa and designed a ritual to go around the Lingam. Ozen, a member of Project Artaud, an artist live-work project, designed a ritual performance around the work. Many consider this to be the inflection point for Burning Man’s trajectory toward an art focused event. (In 1993, Burning Man was technically called the Black Rock Arts Festival, a name that lasted only one year).

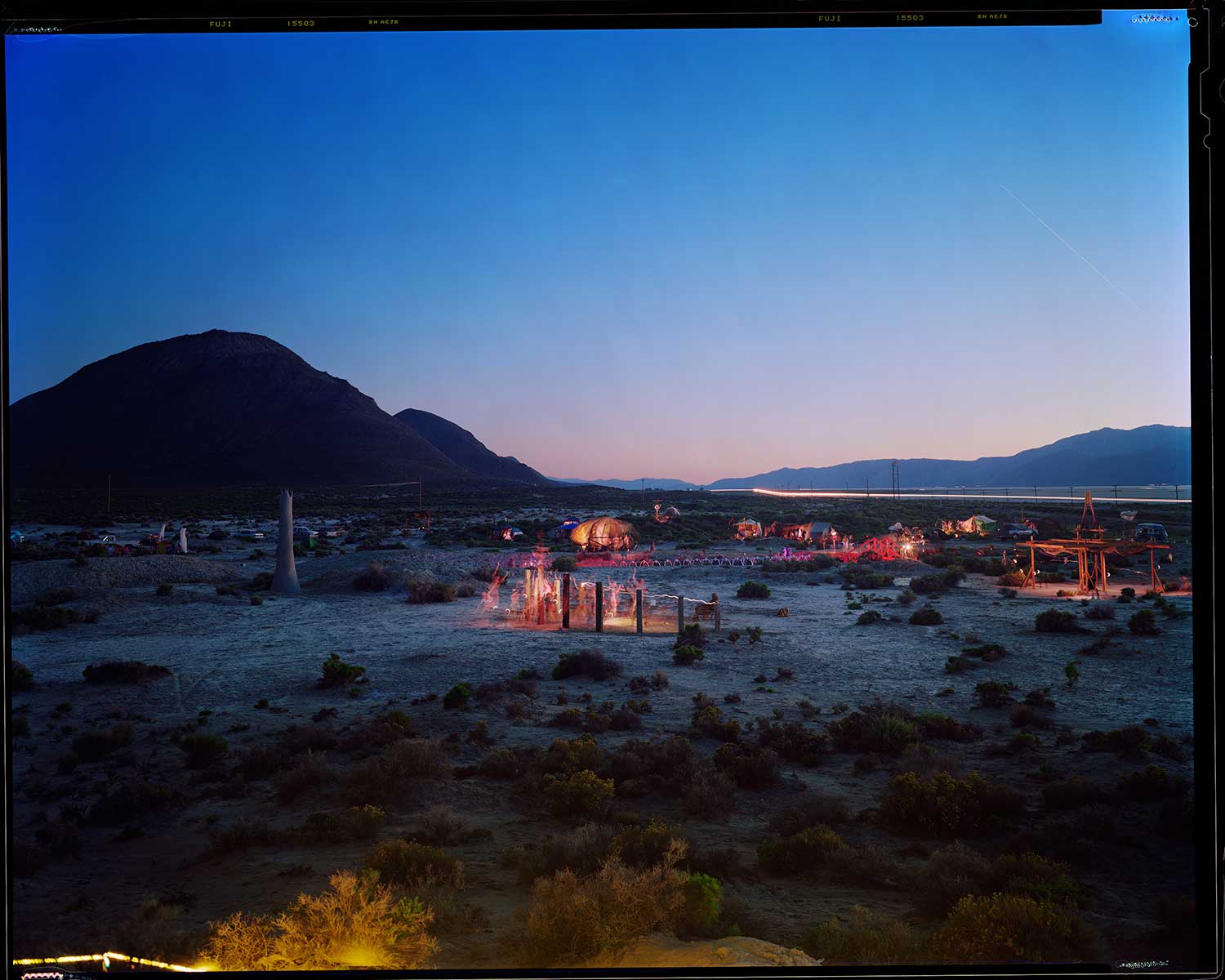

DSW final gathering in 1994 was at Frog Pond Springs at Garett Ranch, where again around 100 people joined together to create art. It was the same week as Burning Man, with the last three days overlapping.

By William L. Fox Director, Center for Art + Environment, Nevada Museum of Art noted:

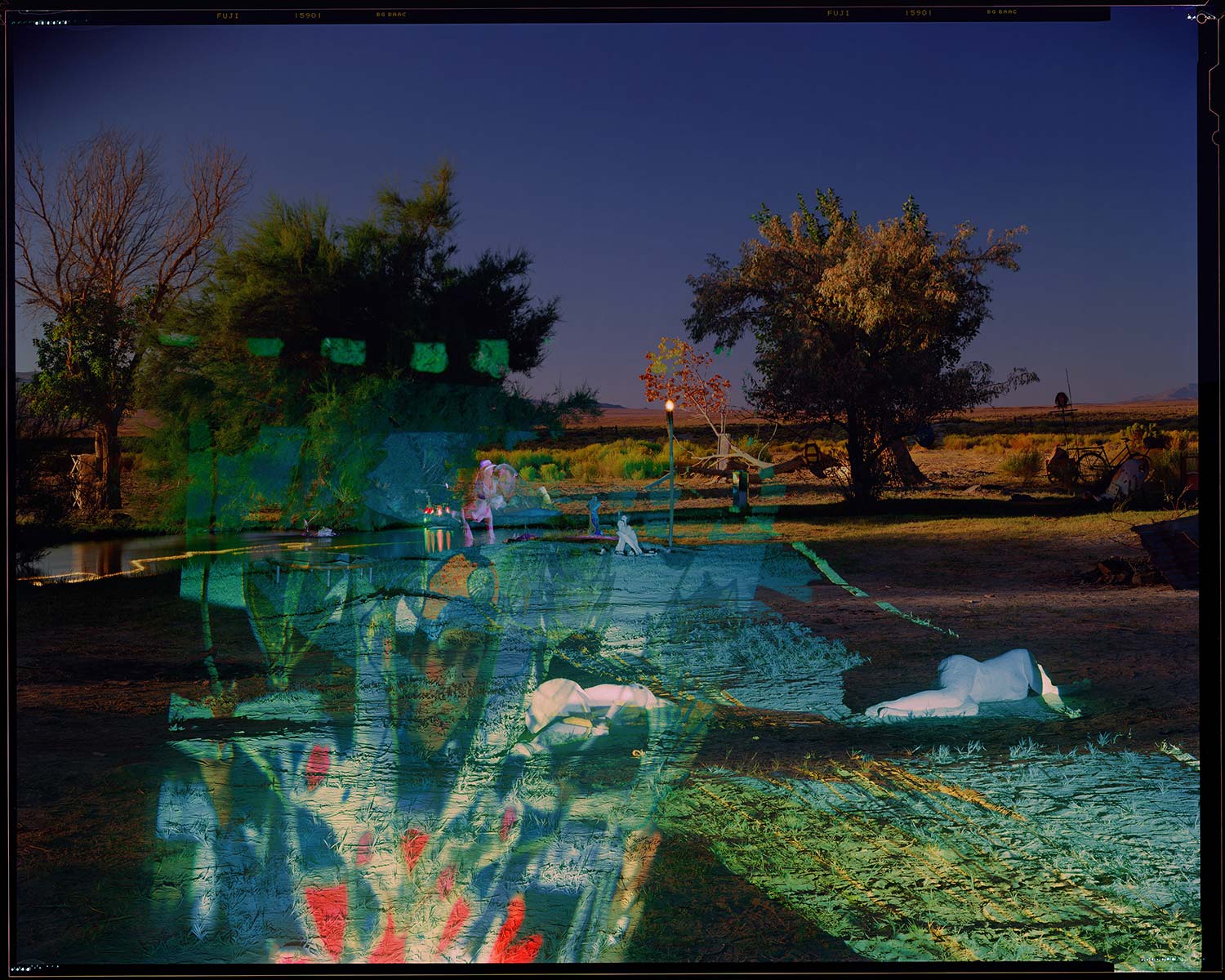

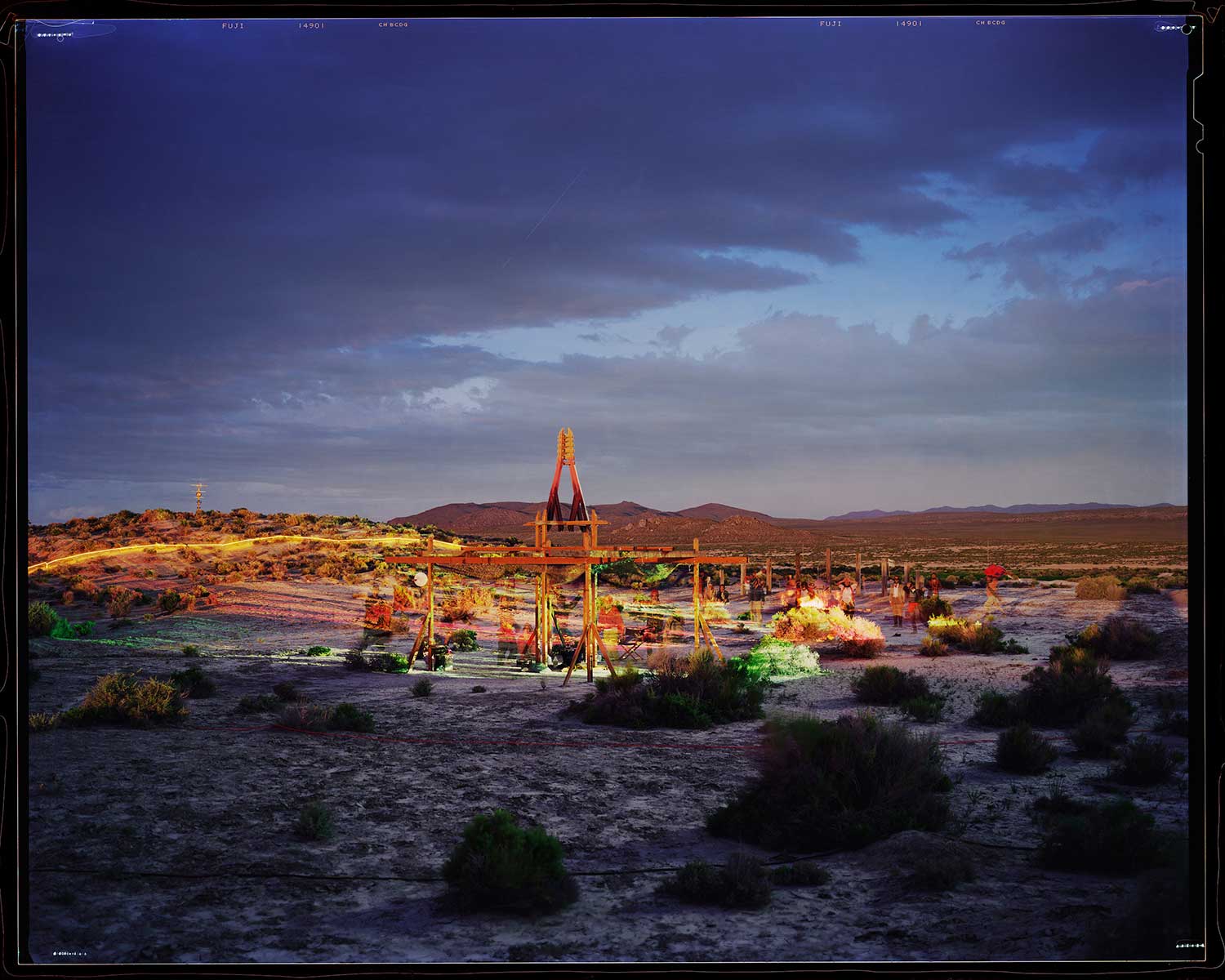

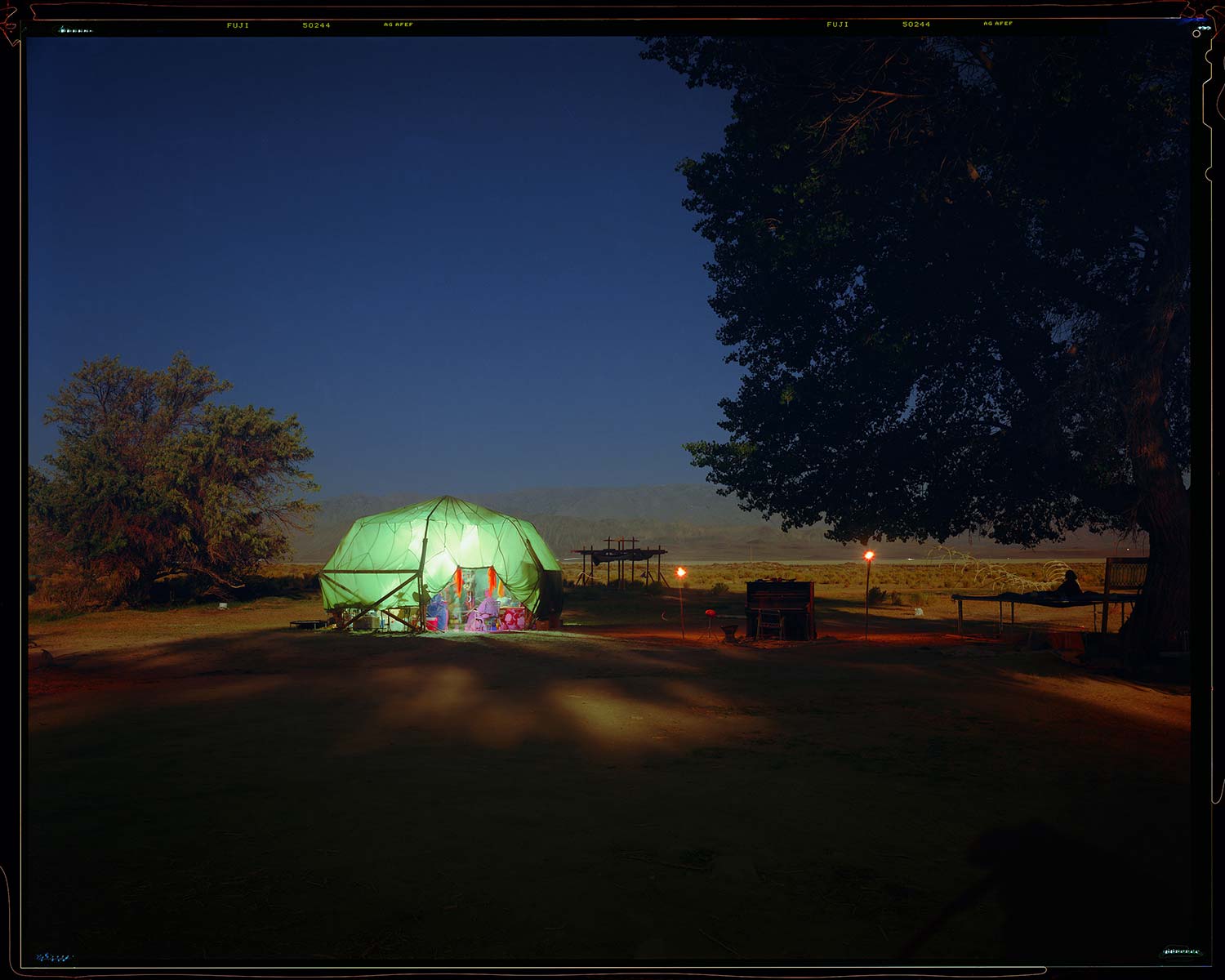

The three Desert Siteworks projects were explorations through performance, architecture and art of the necessities for boundaries and discipline to survive, and even thrive, in an unfamiliar and hostile environment. The inevitable tension between trying to survive and make art at the same time was a method through which people could understand more clearly their relationships to self, to others, and to the environment. Binzen’s photographs—which are few in number because of the amount of work it takes to assemble such artifacts—at their base not only document not only the physical presence of Siteworks in the desert, but also, by virtue of the artist’s degree of manipulation, make manifest how Dada and Surrealism infused the Suicide Club, Cacophony Society, Desert Siteworks, and Burning Man.

Dada and surrealist performances and artworks use randomness and chance in a deliberate fashion, and at heart Binzen’s layered images present us with the essential paradox posed b these earlier art movements: how to create enough order to survive long enough so that we can walk up to the edge of and even into chaos, and then return. There is no successful career as a human without personally experiencing this paradox, and Binzen has given us both a concrete example of how to do so, as well as documents of the process, which is one of the more extraordinary contemporary accomplishments to arise from the Black Rock Desert.

The Photos at DSW

In addition to hosting DSW, Binzen pursued his artistic photography, often taking photos from a ladder, creating pieces with a literal unique perspective, both at DSW and at Burning Man:

I was the only one carting around the playa a stepladder and giant 8-foot tripod. I pulled everything in an oversized trailer behind my bicycle, along with my backpack, clothes and water. When I saw something captivating, I’d start setting everything up and look from above for what Henri Cartier-Bresson called that ‘decisive moment.’

Binzen created his artistic photographs of Siteworks and Burning Man using calculated techniques. “The color effects are very deliberately arrived at,” says Binzen. His intent was to make magical realist images that communicated a deeper reality about the feeling and spirit of the event.

He is admirer of Surrealism, Dada and conceptual art, and became fascinated with “color theory and how to create glow through retinal effects”. Using Adobe Photoshop, he creates up to 40 or 50 layers in each new image, “accentuating the effects of having complementary colors in close proximity to each other.” His textured skies and otherworldly expanses of sand are achieved by painting on glass, “using a variety of oil and aqueous media, hair gel, all sorts of things,” he explains, and then shooting the results.

Influence on Burning Man

Larry Harvey was influenced by Binzen (as was John Law and Michael Mikel), to include more and larger art in the Burning Man gatherings. Since the 1990 meeting at Baker Beach, Harvey and Binzen continued to discuss the direction of Burning Man, and Binzen not only encouraged Harvey to expand the artistic aspect of the event, but also encouraged him to expand the event to a full week, which was working well for the DSW gatherings.

“I talked with Larry (Harvey) for two years, frequently . . .until late at night, about scores of ideas I was gathering from Desert Siteworks about all the art projects we could do in the desert. He listened, and we started steering Burning Man along those lines.”

Pete Ozan not only brought his sculpture to Burning Man, but began to put on large scale operas in the mid-90s. No only was the introduction of larger scale artwork an outgrowth of DSW, but Burning Man fashion was as well. In the early 90s, most people at Burning Man were wearing jeans, t-shirts and shorts (even nudity wasn’t much of a norm until later in the 90s). Paradox Pollack was an early participant in the DSW project, before going on to do choreography for Pete Ozan’s opera. He had founded a performance troupe, Dream Circus, which included fashion statements that bordered on a steam punk and post-apocalyptic appearances and helped influence the fashion statements that began to appear in the mid-90s at Burning Man.

Commenting on the influence of DSW, John Law has noted “The organic costume creations and tribal cohabitation rituals of [Paradox Pollack’s] performance troupe Dream Circus inspired generations of ‘burner fashion; and much of the now commonplace social rituals at the massive, mainstream event. The giant, mud-skinned, steel mesh fire lingam created by the princely, mercurial Pepe Ozan and the attendant wildly primordial and deeply affecting dance ritual evolved into Pepe’s yearly operas, the most powerful and influential collaborative art installations to take place at Burning Man for the next ten years. Pepe’s massive, complex operas predated and inspired David Best’s temples and dozens of future large scale BM collaborations.”

INSIDE "DESERT SITEWORKS"

By WIlliam Binzen

(DATELINE: SUMMER SOLSTICE, 1993 – BLACK ROCK DESERT, NEVADA)

Something's happening here – urban artists are collaborating on projects realized in the desert. Forsaking convenience stores and the studio, they – we – are living and working for periods of time on a remote hotplate of silt and ash, where you can see the curvature of the Earth.

Art in the desert. The question arises, why? And, so what?

Out here, without our exoskeleton (car, gas, cooler, shelter, etc.), we'd be dead meat. Just knowing this, adds an edge. Freedom has a price. It sharpens our sense of what we can and cannot do, tests us. On the playa, mirages recede as we drive, tantalizing us. The last sun rays appear as a laser-thin line, miles long. If you're brain-dead, you won't get inspired. Otherwise ... what can we do in this place? This place where light and heat may cause objects and actions shimmer and stand out in relief, and become altered, taking on new significance, new perception, new inspiration.

Without limits, there is no tension. Without tension, is no progression. Guru Garaj Key

Making art in the Black Rock Desert requires we deal with the vast, vaguely differentiated space of the playa and environs – and define the edges or sets of limits, the context within which art can be convened. Without codes, conventions, sets of limits, there is no language, no consensual reality, no art.

We’re artists in multiple disciplines, we’re performers, musicians and back seat philosophers ready to stand up and spontaneously talk. Here in the desert there is no human audience for our spectacle – we play for ourselves, or to find ourselves, or for amusement, or invention. This is about art as self-discovery, personal and interpersonal healing, and the conjuring of new life-ways, new modes of being & becoming, and sharing culture.

Desert Siteworks was an experiment in site-specific art-making held at desert oases. We came together as a “temporary desert community” (a concept I shared with my friend at the time, Larry Harvey, at Burning Man).

We were large as life, yet by today’s standards, miniscule in scale (just 20 people the first year and a small village of perhaps 100 the second and third). Yet we were art guerrillas at ground zero for the early development of celebratory, earth-based, poly-disciplinary art in the Black Rock. Each year we chose a different hot spring location around the perimeter of the playa: Black Rock Spring (1992), Trego (1993) and Bordello Springs (aka Frog Pond – 1994). In siting a project, we worked with the topography – sand dunes, arroyos, hot springs, dirt roads and scrub – to establish a harmonious layout respecting the terrain and marked by ten of my Desert Navigation Locators.

Fanciful, small villages sprang up, complementing their sites. We encouraged campsite decoration and vehicle camouflage to minimize the presence of ‘standard issue’ cars and trucks (there were no RVs), and to promote the individual camps as artful, as part of the art. We made architectonic sculptures, such as the Desert Yurt (camp center, living room and communal kitchen), the Woodhenge (performance and fire pit), and the Tower Pavilion, (ritual performance), which was based on a Native American swastika if visualized in bird’s eye view.

At Black Rock Spring in 1992 we erected my ‘Desert House’ for the first Desert Siteworks event. It stood symbolically astride the crossroads of the Lassen Applegate (Emigrant) Trail and the main vehicular track up from the playa, Gerlach and the outside world. Later that same year, at Larry Harvey’s request, the Desert House was raised at Burning Man (where it included a working flume by sculptor Greg Schlanger from the University of Nevada, Reno). This was the first art structure besides the Man, and it became a gathering spot (which may have pre-figured Central Camp).

Ritualized performance was a key part of Desert Siteworks. (Pepe Ozan later passed this torch on to Burning Man with his popular operas, which used his Lingams as stages.)

At Trego we experimented with a continuous, 48-hour drama based on the human life cycle from pre-birth to after death. The script was written collectively. We had four directors, each of whom took four-hour shifts and kept the piece going around the clock.

Staging consisted of a single, ceremonial Witness Chair, a portable throne for the benefit of the “Ceremonial Witness" – the Muse of Drama, who held the space and, if necessary, directed the co-evolving, human mosaic of improvised form and sound.

The entire piece was somewhat modeled on the Hero’s Journey and used archetypal systems, such as the Kabbalah and tarot, to explore life and the mind. We moved the Witness Chair wherever the improvisation took us, establishing context and sets of formal limits for the scenes about to play out.

I believe that art had its roots in shamanic healing practices millennia ago. If contemporary art often fails to address substantive issues, the desert is a powerful place to exorcise demons and to reconnect with primal experience poised between Self, Object and Other.

In this context, art is not primarily an abstraction or a market activity or entertainment for a bored or jaded public, but rather a fundamental means of defining our context, our "space" in life -- just as our performance and music mark our "time."

At my suggestion, a number of artists from Desert Siteworks in addition to Pepe Ozan also worked with Burning Man, including Paul Windsor, Al Honig, Paradox Pollack and others.

Desert Siteworks was a weeklong event. This worked well, so I encouraged Larry to do the same (Burning Man at the time was a three-day event). In the fall we took what we had done and learned in the desert back to the city for performances with sculpture in gallery spaces and outdoor venues.

Although under my overall direction, Desert Siteworks was essentially a collaborative venture. We developed our ethos through potlucks every three weeks for nine months before Trego in 1993, and we worked out a kind of guild system with artists and assistants. In the desert we sometimes met in the morning in a circle and passed around a talking stick as we worked to facilitate good communications, to better articulate issues and ideas, and to promote the group process.

Our life in the desert was experimental. What we shared and cross-pollinated challenged us and helped inspire Burning Man’s early (pre-rave) development. Because art that is shared, that affects our lives, that inspires us and is not just a market commodity – matters. It matters a lot. And how we manifest art and how we work out interpersonal issues around this exchange is part of the process, involving both the petty and the significant, age-old dialectic of leadership vs. collaboration.